Scientific consensus is not infallible, but it’s the best approach we have for facing life’s material uncertainties. Following scientific consensus helped me beat cancer (at least for now), and exercising a little faith helped me relax and trust science.

One year ago, I entered an operating room for the first time. An anesthesiologist sedated me, and a surgeon removed a tumor from my neck. I hoped this “excision” would produce a definitive medical outcome. I also hoped it would permanently excise the anxiety that lump had caused before and especially after an inconclusive biopsy. The surgery brought mixed results.

My doctor had not rushed me to the scalpel. He patiently led me through my options over several months, during which I had an ultrasound, a CT scan, the failed biopsy and another CT scan. We discussed the accuracy of each test, the risks posed by surgery, the risks of removing a major salivary gland, and the risks of doing nothing. You’ve heard the term “three-dimensional chess.” Medicine is often a three-dimensional balancing act.

Seeking the Light

After my CT scan, we decided to wait three months and do another for comparison. During this time my anxiety rose. I’m not one for praying or talking about prayer in public, but I will say that I asked God to make the tumor shrink and go away. Three months later, it was unchanged. I asked why. The answer, in so many words: “What makes you special? Millions of people are facing far worse. Maybe you’re asking for the wrong thing.”

I decided to ask instead for inner peace and wisdom to choose the right path. A sense of calm enveloped me almost immediately. The wisdom part is still being decided, in extra innings.

Choosing surgery was made easier, thanks to modern science and my tumor’s accessible location. The surgical risks were small, while leaving the tumor might prove deadly, and living with the uncertainty seemed unacceptable. My doctor revealed he would have made the same decision for himself—the one based on the science.

Facing the Darkness

A few days after surgery, the pathology report showed I had a very rare cancer, Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma (ACC). It was a gut punch. In a single blow, this news confirmed I’d made the right decision, and yet it knocked out my headlights. My path forward was dark. My doctor hadn’t seen a case of this cancer in 17 years and referred me to a regional cancer hospital. Radiation therapy was the likely course, but he did not feel qualified to advise me.

Even before meeting my new doctor, a relative connected me with an ACC survivor who had radiation therapy. She swore that if she had it to do over, she would refuse it because of the side effects. She shared scientific studies casting doubt on its efficacy for ACC. It did not escape me that she was a five-year, cancer-free survivor. How could she know that radiation was not partly the reason she was alive?

I binged medical articles and saw how each study has its own goals, methods and limitations. As a rare illness, ACC data is scarce and clinical trials almost nonexistent. Statistical reviews of past cases struggle to differentiate ACC discovered in different locations at different stages with different growth characteristics. Varied treatments, doses and durations get sliced and diced to predict how long someone may live with or without a recurrence.

Eventually, the only logical takeaway seems to be: Results may vary.

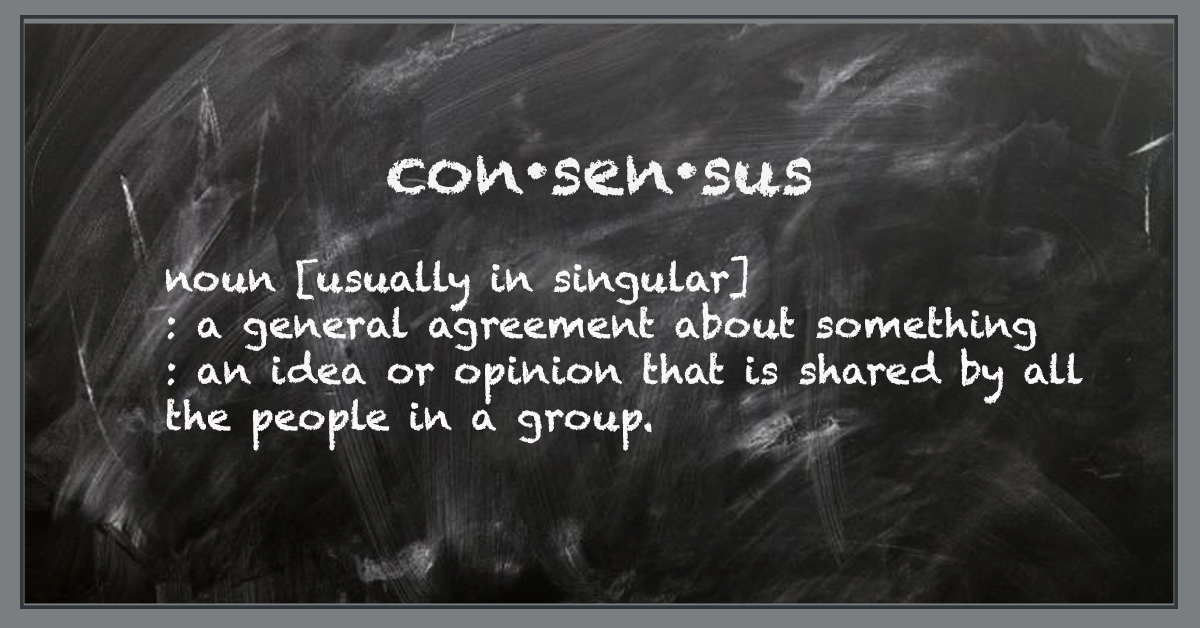

Following the Scientific Consensus

My frustration trying to distill complicated medical articles or evaluate other people’s personal anecdotes turns out to be common. This is why patients should rely on medical specialists who stay abreast of research findings over a long period and form their views in concert with other experts. That is how we get scientific consensus.

Despite hype about conflicting studies (coffee, wine, eggs, climate) there is broad scientific consensus about most thoroughly studied matters. New evidence sometimes upends the consensus. But to flout it, as many are doing today with coronavirus safety guidelines, is foolish and irresponsible. And for politicians to sow doubts about scientific consensus is disqualifying for public service.

My new doctor recommended radiation. It offered the best chance to avoid my biggest risk—a local recurrence from stray cancer cells the surgery missed. More persuasively, the half-dozen members of the cancer hospital’s tumor board unanimously agreed. That’s scientific consensus.

I asked myself: What if I ignored them and later found another tumor in my throat? Would I be willing to admit to people that I flipped off the expert advice of the tumor board?

Yes, radiation was unpleasant. A couple of side effects remain, but all others faded, probably because I followed all the recommendations. And through it all, I learned a lot about myself and the value of every minute of every day.

ACC has a history of returning 20 or 30 years later, so I cannot be pronounced “cured.” One year later, I show “no evidence of disease.” That’s good enough for me. If it changes, I’ll seek expert advice.

My sense of calm remains, and I continue to pray for wisdom. I’ve got so much I still want to do.