GPS history is admittedly a niche interest. Most people don’t care how a technology came about as long as it works, right? But one thing most people think they know about GPS is actually a myth that refuses to die. It’s the zombie notion that President Ronald Reagan declassified GPS, opening the military system for commercial use.

Reagan did no such thing. Proving it is easy. Countering the myth broadly has proven hard. (See the second sentence above.) I rode this particular hobby horse for more than five pages in GPS Declassified: From Smart Bombs to Smartphones, coauthored with Richard D. Easton, and from which I’ve adapted portions of this essay. Of course, books like ours reach only select audiences, and we continue to see the myth perpetuated by big-name media outlets with fact-checkers who should catch it but don’t.

So, let’s review.

Birth of the Reagan Declassification Myth

The Reagan declassification myth has a birthday of sorts—the date of the searing event to which it is tied. September 1, 2023, marks 40 years since the Soviet Union shot down Korean Air Lines Flight KE007. The commercial jetliner had strayed far into Soviet airspace near sensitive military facilities in the dead of night. Experts later surmised the pilots “armed” but never fully “engaged” their navigation equipment—a mechanical setting error.

Despite having triple-redundant inertial navigation systems (INS) on board, the pilot and copilot of Flight KE007 lacked what millions of motorists using GPS today take for granted—the positional awareness that comes from seeing a moving icon on a map. The pilots blindly trusted that the automatic pilot was faithfully executing, with INS guidance, the coordinates they had programmed into it. Instead, they drifted farther and farther off course.

The shootdown killed all 269 souls aboard, including 66 U.S. citizens, among them a sitting U.S. congressman.

In hindsight, we can unpack the factors that helped the myth take root: intensely fraught foreign relations, a military attack on a civilian target, a U.S. president in full PR warfare with the Soviet Union, and the entirely coincidental arrival of GPS—at that time already a decade in development and still another from being declared “fully operational” in 1995.

Reagan was pressing the Soviets on all fronts. Five months earlier, he’d delivered his famous “evil empire” speech and announced his Strategic Defense Initiative, a futuristic antimissile system. He had approved placing nuclear-tipped Gryphon cruise missiles and Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Western Europe to counter the Soviet’s SS-20 missiles. Reagan’s military buildup had pushed federal spending in 1983 to its highest level as a percentage of gross domestic product since World War II.

Reagan’s Response to the Shootdown

Against this backdrop, Reagan worked to marshal world opinion against the Soviets. The U.S. Congress, the International Civil Aviation Association, the International Federation of Air Line Pilot Associations and the United Nations Security Council expressed condemnation through resolutions. (A Soviet veto blocked formal adoption of the UN resolution.) Numerous airlines and entire nations suspended flights to or from the Soviet Union.

For weeks, Reagan mentioned the shootdown in speeches and interviews to draw a stark contrast between Soviet values and behavior and those of democracies. During a televised speech, he played a recording of the Soviet pilot telling commanders, “The target is destroyed.” He devoted a weekly radio address to the shootdown and included it in a speech to the UN General Assembly about the arms race. He called for reparations to the victims’ families and proposed new aviation protocols.

However, in all of Reagan’s public comments about the KE007 shootdown, and in numerous other settings in which he might have strayed onto the subject, he apparently never mentioned GPS. Reagan never issued any public executive order pertaining to GPS. In fact, an online search of his speeches and interviews archived at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library offers no evidence that he ever publicly uttered the phrase “Global Positioning System.”

It seems Reagan’s press secretary, Larry Speakes, made the only official public reference to GPS, while reading a prepared statement before a press conference September 16, 1983. It came at the end of the first paragraph in a brief, two-paragraph text:

“World opinion is united in its determination that this awful tragedy must not be repeated. As a contribution to the achievement of this objective, the President has determined that the United States is prepared to make available to civilian aircraft the facilities of its Global Positioning System when it becomes operational in 1988. This system will provide civilian airliners three-dimensional positional information.”

So, a little-remembered press briefing lies at the heart of the myth.

In Fact

I’m glad Reagan supported GPS and advocated it for civilian flight. But it should be obvious that if this tepid, five-years-to-maturity promise represented a true policy departure or a substantive near-term improvement in airline safety, Reagan would have talked about it himself. A lot.

Making the offer not only required no declassification, but it was also technically unnecessary. From the earliest days of planning a navigation satellite system, government officials planned for civilian use.

In 1970, an interservice committee called the Navigation Satellite Executive Steering Group (NAVSEG) tried to resolve differing needs among the Army, Air Force, Navy, and civilian air traffic control (ATC). The services had conflicting requirements but generally wanted a passive system that broadcast signals without the user having to activate it by transmitting a signal that would disclose their location. Civil ATC envisioned an interactive system with continuous aircraft communication.

Furthermore, private industry was content to let the government bankroll the novel and expensive system, which during the 1970s struggled to win funding from Congress or even unanimous support within the military.

John McLucas, secretary of the Air Force when the GPS program began, left that post in 1975 to head the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for two years. Despite being such a strong proponent of the system that he ordered a vanity license plate that read “GPS NOW,” he later admitted, “I could not get the FAA interested in GPS.”

The interservice Joint Program Office that led GPS development nevertheless built the system from the start to serve dual military and civilian use:

“The P Signal is used by the precision military user and will resist jamming, spoofing, and multipath and will be deniable to unauthorized users by employing transmission security (TRNSEC) devices. The C/A Signal will serve as an aid to the acquisition of the P Signal and will also provide a navigation signal in the clear to both the military and civil user.” (Italics added for emphasis.)

— from page 30, Navstar Global Positioning System Program Management Plan, July 15, 1974.

In any case, as Speakes made the announcement, all six GPS satellites orbiting overhead already broadcast two signals—one for the military and another for civilians. As we show in our book, Texas Instruments marketed a commercial GPS receiver to land surveyors in 1982, a year before the airliner incident.

I rest my case.

Epilogue

Research has shown it is difficult to dislodge false beliefs once they have taken hold. Older folks who remember the 1983 KAL shootdown are probably not searching the topic online. If a question arises about how civilians began using the military’s GPS system, they assume they know the answer.

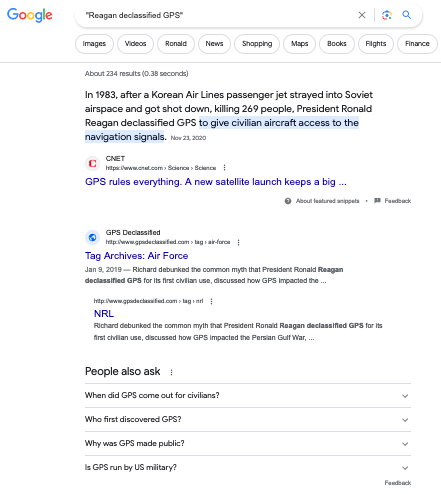

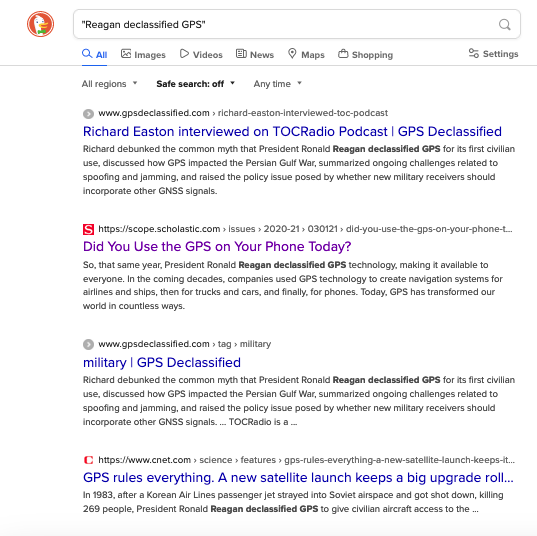

For a decade, Richard and I have worked to quash the Reagan declassification myth and other GPS myths in public talks, published articles, media interviews, blog posts and podcasts. Progress is slow. For example, on September 7, 2011, I performed a Google search of the term “Reagan declassified GPS.” It yielded 319 results. Twelve years later, on August 6, 2023, the same search produced 234 results.

However meaningful the lower results number, a screenshot of the Google search shows the myth remains the top result. That was depressing, but then, I performed the same search using DuckDuckGo (Bing). This time the top result was a post about Richard debunking the myth. It seems like a small win, but we’ll take it.

Perhaps our repeated recitations of the facts disproving the Regan declassification myth will help younger people, newly curious about GPS and its origins, to find and learn the truth rather than the myth.