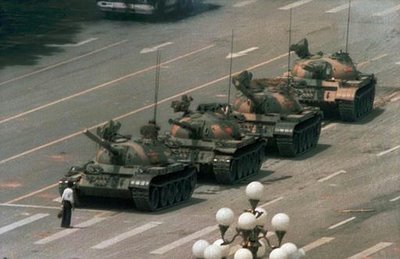

European courts ruled recently that people have the “right to be forgotten.” What about the right not to be forgotten? Does that not apply to Tiananmen Square, where thousands of unarmed protesters were killed 25 years ago by their nation’s own troops, a popular uprising literally crushed by tanks?  China’s government today censors Internet searches, trying to scrub the collective memory of the atrocities it committed.

China’s government today censors Internet searches, trying to scrub the collective memory of the atrocities it committed.

Whitewashing history is not new, but the methods are evolving.

After the June 4, 1989, massacre, New Star Publishing, a state-approved outlet, released “The Beijing Riot: A Photo Record.” Both the imagery chosen for the 24 officially sanctioned photos and the laughable propaganda in the captions speak volumes about the old adage that “history is written by the victors.” The protests were led by “thugs” and “ruffians,” who “incited innocent people” by “fabricating rumors.”

While one caption acknowledged that “more than 3,000 civilians were wounded and over 200 died,” it claimed that “not a single corpse” was found while cleaning up Tiananmen Square. A disproportionate number of the photos focus on the Red Army cleaning up garbage left behind, and others push the notion that most protesters voluntarily withdrew from the Square.

While first drafts of history are often biased or flawed, relentless research and revision by multiple historians can eventually arrive at a generally accepted view—or at least a range of competing viewpoints. BUT, this can happen only where freedom of speech and of the press are respected. Honest history cannot survive where researchers cannot access documents. I find it hard to distinguish between blocking Internet sites and padlocking libraries or burning books.

Five years ago, on the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen protests, Chinese officials launched such an extensive effort to censor online material about the uprising that more than 300 web services were shut down, ostensibly for “maintenance.” June 4 became mockingly known as “Internet Maintenance Day.”

However, as each anniversary passes, Chinese censors add new keywords and combinations of Chinese, English and Latin characters and even Roman numerals to their growing list of blocked search terms. Brute force shutdowns are yielding to more sophisticated filtering.

Advances in artificial intelligence can only exacerbate these trends, enabling Internet censorship to spread. And increasingly, the reports and documents on which historians depend originate in digital form. That’s why I worry about the European ruling, which allows individuals to petition Google or other search services to remove links to embarrassing information, such as a past bankruptcy. “Corporations are people, too, my friend,” Mitt Romney famously said. Why not allow companies to block search engine results? Where might it stop?

We must be vigilant, or we will live to see history stolen by stealth.